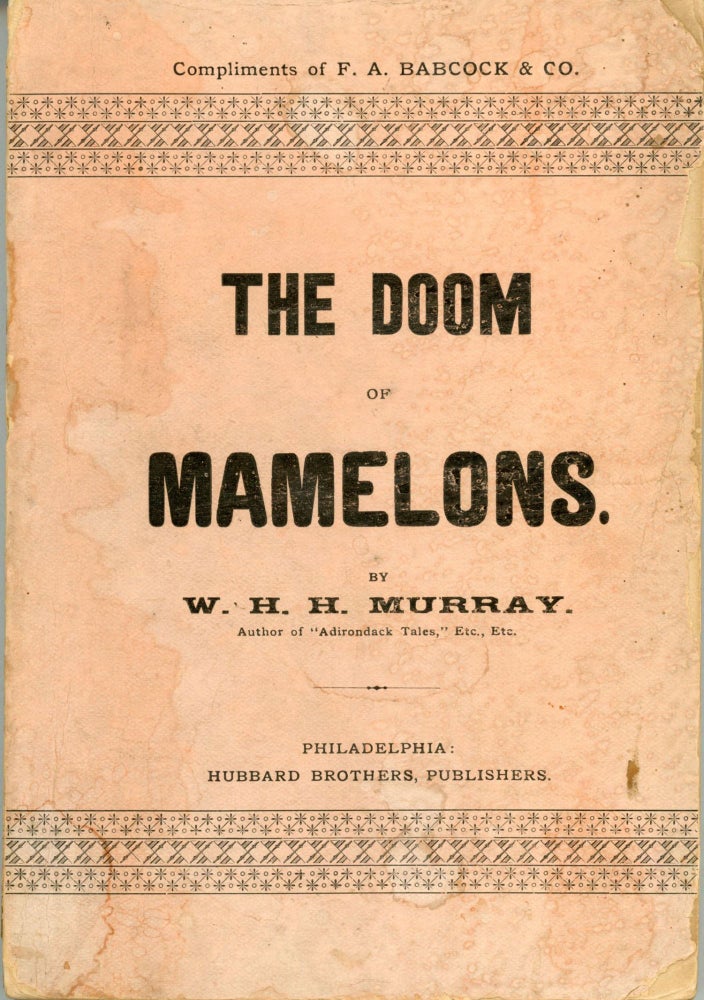

THE DOOM OF MAMELONS: A LEGEND OF THE SAGUENAY. Philadelphia: Hubbard Brothers, Publishers, 1888. Octavo, pp. [1-4] i-iv 3-136 [137-138: blank] [note: preliminary leaves erratically paginated], original salmon wrappers printed in black. First edition, promotional issue. This variant printing differs from the other Hubbard version which is also dated 1888 on the title page. It adds a four page introduction (here called an "argument" by Murray which follows his one page "preface" dated 7 January 1888. We do not know which printing is the earliest. This copy is part of a promotional issue with "Compliments of F. A. Babcock & Co." printed at the top edge of the front cover and an illustrated advertisement for their carriages and carts on the inside rear cover. A romantic novella with supernatural incidents and a pervading mood of otherworldly gloom and glory, autumnal in its mix of the sweet and the bitter, an elegy to the Old World that was dying in the birth throes of the New. Set in the backwoods of Quebec in an indefinite past, perhaps the colonial period, this is the story of John Norton, the heroically noble and simple trapper who was a recurring character in Murray's tales, and Atla, the beautiful and cultured princess and last of her line of Basque royalty. It is her hope to marry the trapper and start a new and more vital branch of her race, but a doom overhangs her and her people and cuts off the consummation of their romance. The background of the story is told in retrospect, through the narration, "half-chanted," of Atla's dying uncle, whose summons has brought John to their island mansion; and through the poetic words of her dead mother, found on a manuscript and read aloud by Atla. The Basques of the Iberian peninsula are represented in the story as the oldest race of Europe and, indeed, of the world, long established by the time the Egyptians began hauling blocks of stone over desert sands, and frequent visitors to North America. It is hinted by Murray that they are related to the mound builders, that shadowy race of advanced pre-Indian civilization in America, and that they were in fact, a remnant of the civilization of Atlantis -- and even more anciently, of the crossbreeding of gods and men referred to in Genesis (6:2). At some time in the recent past, an epic battle was fought between rival Indian tribes at Mamelons, the mouth of the Saguenay river, whose waters ("purple-brown … gloomy and grewsome") lead into the St. Lawrence. In the battle, the ghosts of slain warriors on both sides rose up and fought side by side with the living, and nature warred against itself with storm and earthquake, until God brought the battle to a halt with a sudden total darkness. Afterwards it was discovered that Atla's uncle, chief of his tribe, had inadvertently killed his own brother, the father of Atla. He marries the widow and raises Atla lovingly as his own, even after the subsequent and untimely death of her mother. She is only 20 when her uncle dies and she is left alone in the world, though the heiress of a great fortune and vastly learned in antique lore. Her proffer of marriage encounters resistance from the 40-year-old trapper, who considers himself unworthy of her, but she finally wins him over. On their way back to Mamelons to be wed by the Catholic priest, a warning from their old Indian servant, who has seen a supernatural omen, is ignored, leading to the death of Atla on the shores of the Stygian Saguenay. The story is a meditation on matters of race and fate, especially germane to the American experiment of embracing cultural heterogeneity. The plot hangs on some rather complicated taboos about breeding, which will seem esoteric to most modern readers. An individual of mixed breeding is said to "bear a cross." Yet the doom hanging over Atla's race, a divine punishment for crossbreeding, can be removed only by her crossbreeding with an individual of purebred stock (Norton being white without taint of any other strain). But the story bears no whiff of "racism" in its generally understood sense, and shows a deep knowledge of and respect for the various Indian tribes, as well as, in passing, a curious veneration for Jews, not on the usual scriptural grounds as precursors of Christianity, but on purely racial grounds. The theme of crossing also characterizes certain aspects of Murray's own writing. With its frequent use of explanatory footnotes, the work crosses fiction and nonfiction. It crosses the archetypal with the highly specific. In its values, it embodies a Yeatsian admiration for both the primitive and the esoteric, peasant and aristocrat, while disdaining everything in the middle and everything that is modern or mongrel. In its style, the writing embodies its own nostalgia for the past. The epic similes carry with them echoes of Homer, and the heavy alliteration, of Old English epics. The conversations have sometimes the formality of a catechism. Whole sentences sometimes fall into an iambic chant. Overall, the work reads like a product of the Celtic Twilight, which was then starting to appear in Ireland, and in a sentence like, "What are books but oral knowledge spread out in words which lack the fire of forceful utterance?" we could almost be listening to Yeats. After speaking on behalf of the old ways of her race and their celebration of the old gods, Atla acquiesces to Norton's Christianity, with its emphasis on the afterlife, and she speaks, "In this thy faith is better -- it hangs a star above the tide of death for love to steer by." It is a sentence not unworthy of Yeats. The book is remarkable as a stylistic exercise. It also foreshadows Machen's mingling of the weird and the martial in "The Bowmen" (1914). And it is noteworthy as an example of the Last Man motif, harkening back to THE LAST OF THE MOHICANS (1826) and ahead to GREEN MANSIONS (1904), and to the more pronounced expressions of the motif in such works as Mary Shelley's THE LAST MAN (1826) and Shiel's THE PURPLE CLOUD (1901), and, of course, the more diffuse expressions found in the lost race genre which had just crystallized around Haggard's SHE (1887) a year before the publication of this book. The novella was republished in 1890 in MAMELONS AND UNGAVA, the latter being a sequel which is even more overtly supernatural and which also had an earlier separate publication (in 1889). All in all, a very interesting and unjustly overlooked work. (Reading note by Robert Eldridge). Not in Bleiler (1948; 1978) or Reginald (1979; 1992). Wright (III) 3907. Covers chipped at corners, 35x10 mm chip from the fore-edge of the rear cover, some fading and staining to covers, a good copy. (#165913).

Price: $100.00

No statement of printing.