Introduction by Michael L. Ciancone

(Adapted from Ciancone's "Introduction" to Foreword to Spaceflight: An Illustrated Bibliography of pre-1958 Books on Rocketry & Space Travel [Apogee, 2018].)

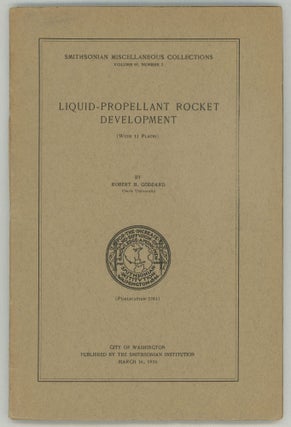

Three men are widely recognized as the fathers of rocketry for spaceflight—Konstantin Tsiolkovskii (Russia), Hermann Oberth (Germany), and Robert Goddard (United States). Tsiolkovskii developed the theory underpinning human spaceflight and wrote small books on space travel and cosmology (the expansion of humans into the cosmos). The “holy grail” of this genre is an article he wrote in the May 1903 issue of “Nauchnoe Obozrenie” [Scientific Review] on “Exploration of Space by Means of Reactive Devices” in which he established the “rocket equation” and addressed various aspects of future spaceflight. Tsiolkovskii was influential as a mentor and inspiration to experimenters and spaceflight advocates in the Soviet Union. Oberth was also an early theoretician who was well-known to early rocket pioneers in Europe and beyond. He tried a bit of experimentation, but he was a better writer than scientist or engineer. Oberth wrote one of the most influential books on spaceflight—Die Rakete zu den Planetenrӓumen (Oldenbourg, 1923)—which inspired a generation of “rocketeers” around the world. Goddard, on the other hand, was an experimenter who spent his life building and testing rockets. He published his seminal monograph, A Method of Reaching Extreme Altitudes, in 1919 through the Smithsonian Institution and launched the first liquid-fuel rocket in the world on 16 March 1926.

What began as a solitary endeavor grew, as people with similar interests formed small groups to share news and plan for the future. Writers, particularly during the formative years of the 1920s and 1930s, were the publicists who used their medium to spread the “gospel” of spaceflight and to explain what it offered to the future of mankind. These visionaries were able to take the dreams of spaceflight and weave them into stories for public consumption. The first book of non-fiction in English on the use of rockets for human spaceflight, The Conquest of Space (Penguin Press, 1931), was written by David Lasser, a founder and the first president of the American Interplanetary Society (later re-named the American Rocket Society, which exists today as the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics). The first British books of this genre appeared shortly thereafter—Stratosphere and Rocket Flight (Astronautics) (Pitman, 1935) by C.G. Philp and Rockets Through Space—The Dawn of Interplanetary Travel (Allen and Unwin, 1936) by P.E. Cleator. Although many of these early rocketeers tended to be writers, they were soon augmented by technical members, such as engineers, who were interested in the practical application of rocketry to human spaceflight. Together, these groups of dreamers and doers provided a fertile breeding ground that merely awaited a catalyst.

Certainly, it has to be said that it was extremely important to the development of rockets when the military became interested. This took rockets from the realm of the amateurs and into the arena of military applications. However, there is also a price to pay for relying on military support for a particular technology, whether it is atomic energy or rocketry. Technology is a sword with two edges that cuts in both directions. Rockets that fulfill dreams of launching humans into space are also potential weapons of war. This is a dilemma with which rocketeers have struggled. But it is a legacy that we must acknowledge and understand.

The development of the A-4 (V-2) rocket by Germany during World War II was a catalyst for rocket development in the United States and the Soviet Union following World War II. One of the most interesting contemporary books on the V-2, Ballistics of the Future by Kooy and Uytenbogaart(Stam, 1946), provides detailed schematics of the V-2 rocket and the location of launch sites in The Netherlands.

Early rocket experimenters were pleased to see their rockets launch into the sky without exploding. Then they were eager to send their rockets higher and farther. The destination was unimportant, other than “up.” Later, it became important to control the flight of the rocket with an intended destination. To advocates of human spaceflight, this destination took the form of placing a spacecraft into orbit around the Earth, or sending it to the Moon or Mars. Perhaps the most influential book on this theme was The Mars Project (University of Illinois Press, 1953) by Wernher von Braun, who was an early member of the German Society for Space Travel and architect of the V-2 rocket program in World War 2, and later a prominent figure in the US space program.

Cold War tension between the United States and the USSR led to the space race—space was the new field of competition in a battle of ideologies. The initial venue for this competition was the International Geophysical Year (IGY) during which nations of the world were encouraged to join together to explore and better understand the Earth. At this same time, the United States and the Soviet Union were both eager to develop intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). IGY offered a convenient opportunity to sustain rocket development in support of the launch of the first artificial satellite into orbit around the Earth, ostensibly for peaceful purposes.

Like a bicycle race, the space race was a race of stages. The Soviet Union won the first “stage” with the launch of Sputnik on 4 October 1957. And it won other stages as well, representing major milestones, such as the first human in space (with the launch of Yuri Gagarin on 12 April 1961). But on 20 July 1969, the United States became the first nation (and thus far, the only nation) to land humans on the Moon.

These achievements generated a lot of public interest, which resulted in many publications about those achievements. Before the launch of Sputnik, there had only been a few hundred books published of speculative nonfiction on human spaceflight since the early 1900s. Most of these appeared in English and German, but there were also books published in Russian, Italian, French, and Spanish. After the launch of Sputnik, the number of books about spaceflight increased significantly as people around the world sought information on efforts to explore this ultimate frontier.

An early chroniclers of the history, current status and future of human space flight was Will Ley, who escaped Nazi Germany in 1935. He is perhaps best known for Rockets, Missiles and Space Travel, which first appeared as Rockets—The Future of Flight Beyond the Stratosphere (Viking, 1944), and went through many editions and printings under different titles through the 1960s.

The history of spaceflight is still being written as mankind continues its journey, back to the Moon and on to Mars.

![#163929) THE DESIGN OF A STRATOSPHERE ROCKET ... [cover title]. Alfred Africano](https://lwcurrey.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/163929.jpg?width=320&height=427&fit=bounds&auto=webp&v=1682013692)

![#142811) L'ASTRONAUTIQUE [and] L'ASTRONAUTIQUE COMPLÉMENT. Robert Esnault-Pelterie](https://lwcurrey.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/142811.jpg?width=320&height=427&fit=bounds&auto=webp&v=1682007980)

![#163920) ROCKETS: NEW TRAIL TO EMPIRE. REVIEWS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY. Second Edition [cover title]....](https://lwcurrey.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/163920.jpg?width=320&height=427&fit=bounds&auto=webp&v=1682013688)

![#163922) ROCKETS: NEW TRAIL TO EMPIRE. REVIEWS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY. Second Edition [cover title]....](https://lwcurrey.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/163922.jpg?width=320&height=427&fit=bounds&auto=webp&v=1682013689)

![#135435) FLUGBAHN-BERECHNUNG EINES ZWEISTUFIGEN RAKETEN-MODELLS [cover title]. Hermann Langkrär](https://lwcurrey.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/135435.jpg?width=320&height=427&fit=bounds&auto=webp&v=1682006566)

![#139573) LES FUSÉES VOLANTES MÉTÉOROLOGIQUES ... [cover title]. Willy Ley, Herbert Schaefer](https://lwcurrey.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/139573.jpg?width=320&height=427&fit=bounds&auto=webp&v=1682006570)

![#162935) LUNARIUM [text in Russian]. E. Parnov, L. Samsonenko](https://lwcurrey.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/162935.jpg?width=320&height=427&fit=bounds&auto=webp&v=1682013814)

![#163928) WHAT'S IN THE ROCKET? ... [cover title]. G. Edward Pendray](https://lwcurrey.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/163928.jpg?width=320&height=427&fit=bounds&auto=webp&v=1682013692)

![#160316) MEZHPLANETNYE PUTESHESTVIIA [INTERPLANETARY TRAVELS]. Iakov Isidorovich Perel'man](https://lwcurrey.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/160316.jpg?width=320&height=427&fit=bounds&auto=webp&v=1682012409)