THE DARKEST SEASON OF THE YEAR

By Boyd White

"… even if the U.S. never acquired the English tradition of ghostly tales at Christmas time, I like ‘em. Far better way to spend an evening than going out shopping."

— Karl Edward Wagner, letter to Richard Fawcett, 3 December 1984

"The story had held us, round the fire, sufficiently breathless, but except the obvious remark that it was gruesome, as on Christmas Eve in an old house a strange tale should essentially be, I remember no comment uttered till somebody happened to note it as the only case in which such a visitation had fallen on a child."

— Henry James, The Turn of the Screw (1898)

No one can say with certainty when the tradition of telling ghost stories at Christmas first originated. The concept of spirits walking the earth at specific times of the year was a feature of holiday festivals around the world long before the advent of Christianity. Since ancient times, Winter Solstice, usually December 21 or 22, the darkest and longest day of the year, has long been considered an instance when the barrier between the worlds of the living and the dead becomes somewhat permeable, providing restless spirits with access to humankind. Even today, non-Christian midwinter festivals, such as the Iranian Yaldā, center around gatherings of family and friends who stay up all night eating, talking, and sharing stories to stave off the dark forces that may be about. Such features also characterized early pagan festivals like the Germanic Yule, a 12-day celebration connected with belief in the Wild Hunt, a procession of ghostly hunters in wild pursuit across the night sky that supposedly foretold catastrophes, such as plague or war, or the abduction of people to the underworld or to the realm of fairy. King Haakon I of Norway Christianized Yule in the 10th century when he rescheduled the dates for Yule to coincide with Christian celebrations. To this day, the Christmas season retains traditional features of Yule, including the Yule log, the Yule ham, and Yule singing. When we consider that Christmas follows soon after the observance of Allhallowtide from October 31 to November 2, a combination of ancient Celtic harvest festivals and Christian celebrations associated with restless souls and remembering the dead, fall and winter holiday traditions, particularly Christian ones, have always clearly had a touch of the uncanny.

The use of cold, wintry settings for depictions of encounters with the supernatural is a feature of both early oral and written storytelling. In the Old English epic Beowulf (circa 700 to 1000), Grendel's raids upon Herot Hall take place at night over the course of twelve long winters while King Hrothgar's subjects are sleeping around the hearth after indulging in celebratory feasts. Likewise, in the 13th-century Icelanders' Grettir’s Saga, the troll attacks that Grettir wards off occur on Christmas Eve. By the time William Shakespeare's pens The Winter's Tale in 1611, setting supernatural stories in winter has become an accepted convention; in Act 1, Scene 2, when Hermione, the queen of Sicily, asks her young son Mamillius to entertain her with a story, he replies, "A sad tale's best for winter. I have one / of sprites and goblins." 17th-century England also provides one of the clearest historical examples of the association of the supernatural specifically with Christmas: the reported sightings in 1642 just prior to the holiday of spectral Royalist and Parliamentarian forces re-enacting the Battle of Edgehill, the first conflict of the English Civil War, in the night sky near Kineton. Seen by shepherds, the local priest, and numerous villagers, sightings of the phantoms--complete with screams of horses, clashes of weapons, and cries of the dying--were so numerous over a period of successive days that Charles I sent royal emissaries to investigate the situation; they themselves also attested to witnessing the same ghostly battle, even identifying certain participants. To stop the apparitions, villagers eventually buried all the corpses that had remained strewn across the battlefield since the conflict had taken place on October 23. The story of the Edgehill ghosts was soon memorialized and spread through the publication of a pamphlet in January 1643 entitled A great wonder in heaven shewing the late apparitions and prodigious noyse of war and battals, seen on Edge-Hill, neere Keinton, in Northamptonshire 1642. Similar to the legend of the Edgehill ghosts, as Keith Lee Morris notes in "Christmas Ghost Stories: A History of Seasonal Spine-Chillers," Mary Shelly's Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818) and Edgar Allan Poe's "The Raven" (1845) are prime examples of winter's tales. Shelly's novel opens aboard a ship in the Arctic in the month of December, and Poe's raven confronts the narrator in "the bleak December" when "each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor." In both the United States and Great Britain, by the early 19th century, winter and all things ghostly were defining aspects of foundational works of supernatural literature.

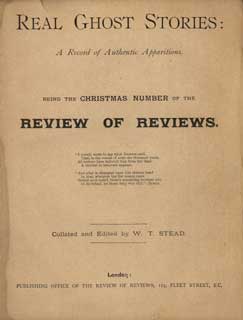

Critics and scholars regard the Victorian era, particularly the period from 1850 to 1902, as the high watermark for the development of the ghost story. In her seminal study Night Visitors: The Rise and Fall of the English Ghost Story (1977), Julia Briggs emphasizes how the Victorian ghost story's "remarkable success was closely connected with the growth of a reading public who consumed fictional periodicals avidly, magazines such as Blackwood’s, the Cornhill, Tinsley's, Household Words, All the Year Round, Temple Bar, St. James, Belgravia, and The Strand … The predominantly middle-class audiences enjoyed romance and pictures of high life, but also liked to read of familiar settings transformed by a sudden eruption of crime, violence, or the supernatural. Ghosts, like detectives, commonly operated in middle-class homes." With a formulaic approach that was easily repeatable, ghost stories were often used as filler alongside longer works serialized in magazines, and as the popularity of the genre grew steadily, "more talented writers," as Briggs notes, "began to explore the ghost story's possibilities as a serious literary form." Somewhat predictably, the rise of the ghost story during the Victorian era corresponded with an increased public interest in spiritualism, including séances and spirit photography, the practice of photographing sitters with deceased loved ones, cultural phenomena that clashed with rapidly increasing scientific and technological progress that, combined with Darwinian theory and Freudian psychology, threatened to strip the world and human existence of any sense of mystery or wonder. "True" accounts of ghost sightings and other spiritual phenomena, such as Catherine Crowe's The Night Side of Nature: Ghosts and Ghost Seers (1848) and Frederick George Lee's The Other World: Glimpses of the Supernatural. Being Facts, Records, and Traditions Relating to Dreams, Omens, Miraculous Occurrences, Apparitions, Wraiths, Warnings Second-Sight, Witchcraft, Necromancy, Etc. (1875), were immensely popular. Viewed in this context, fictional and factual ghost stories during the Victorian era embodied the tension resulting from outmoded but not entirely abandoned traditional religious and/or supernatural systems of belief being displaced by reason and rationalism, as well as the erosion of the individual and the communal through industrialization and urbanization.

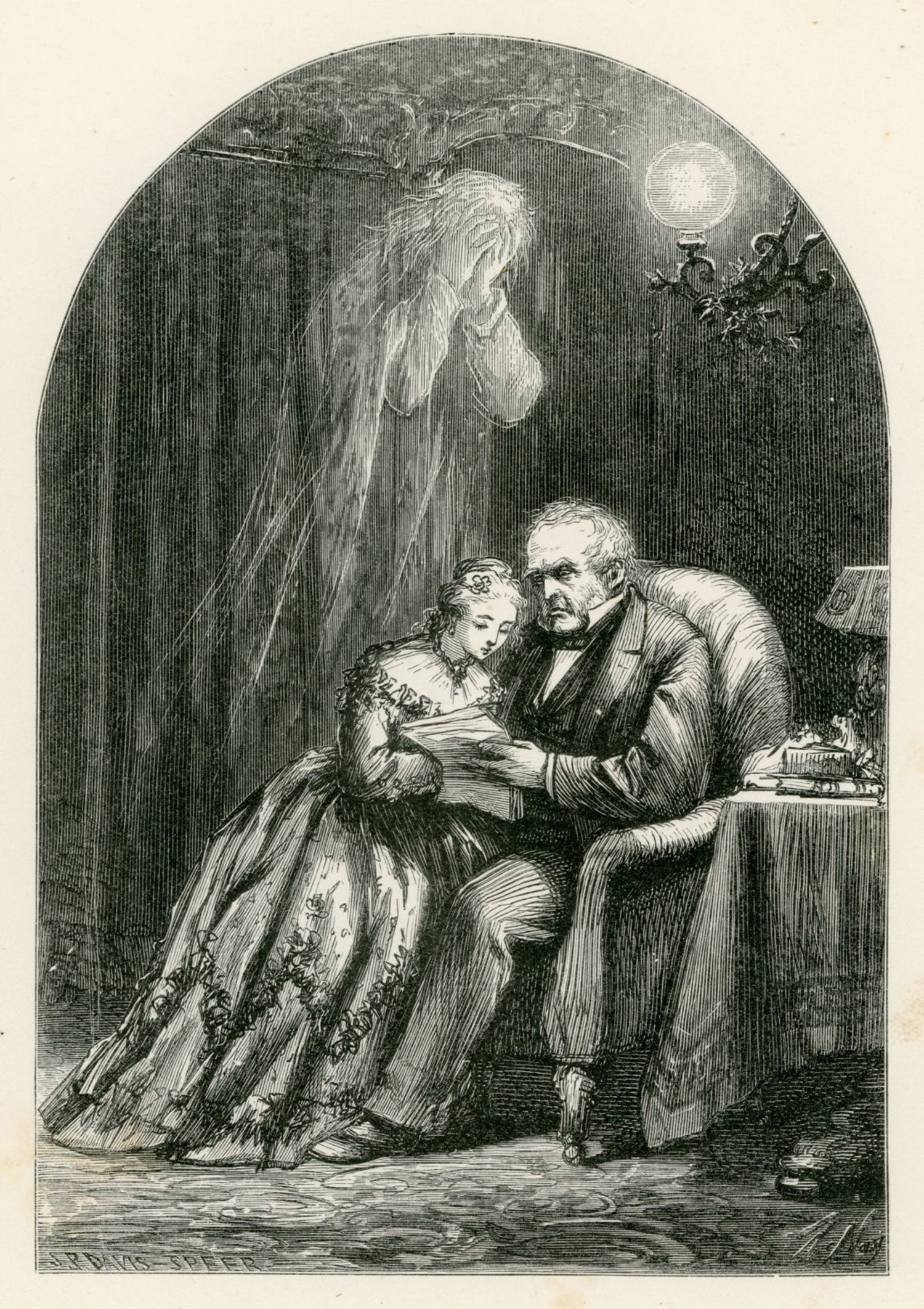

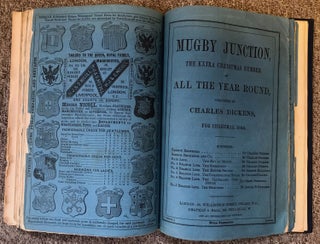

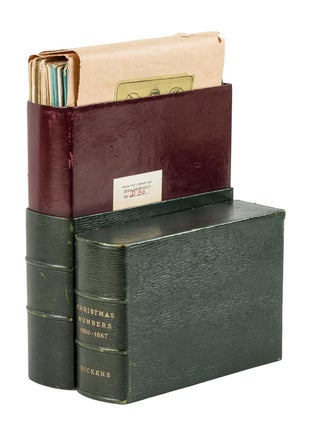

Amidst these swirling cultural forces, Charles Dickens, as Briggs so astutely observes, "revived the traditional connection of ghosts with Christmas through the custom of telling ghostly stories on Christmas Eve." A savvy writer and editor with a knack for spotting and establishing commercial trends, Dickens had already included several chapters in The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club (1836-37) that featured supernatural stories, but the publication in 1843 of Dickens' A Christmas Carol. In Prose. Being a Ghost Story of Christmas ushered in the golden age of the ghost story as a literary form. The success of A Christmas Carol led to a host of Christmas books, fantasies--often ghost stories--with clear moral objectives, including Dickens' The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain: A Fancy for Christmas-Time (1848) and others that today are virtually forgotten like Frederick William Robinson's Twelve O'Clock. A Christmas Story (1861). The popularity of Christmas books soon gave birth to the Christmas annuals, special supplementary issues of popular magazines for which Dickens set an incredibly high standard with the Christmas numbers of Household Words (1950-1858) and All the Year Round (1859-1867) that he edited.

By creating narrative and thematic frameworks for the stories he solicited from his fellow writers for his Christmas annuals, Dickens firmly established the late 19th-century literary convention of ghost stories being told at gatherings of family and friends or by traveling companions on holiday trips, a conceit that has its roots in Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales (circa 1387-1400), particularly Chanticleer's lecture on the significance of dreams and apparitions in "The Nun's Priest Tale." The titles of Dickens' Christmas annuals are transparent in terms of their linking devices, such as A Round of Christmas Stories by the Fire (Household Words, 1852), The Haunted House (Household Words, 1855), Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings (All the Year Round, 1863), and the railway-themed Munby Junction (All the Year Round, 1866). Given Dickens' editorial acumen, the stories featured in his Christmas annuals constitute a veritable roll call of some of the most brilliant Victorian ghost stories, including Elizabeth Gaskell's "The Old Nurse's Story" (Household Words, 1852); Amelia B. Edwards' "The Phantom Coach" (All the Year Round, 1864) and "The Engineer's Story" (All the Year Round, 1866); and Dickens' own "To Be Taken with a Grain of Salt" (All the Year Round, 1865) and "The Signalman" (All the Year Round, 1866). Dickens' influence, in fact, on the overall shape and direction of Victorian supernatural literature extends far beyond just the traditional ghost story. His Christmas annuals include superb examples of key types of horror fiction, such as Wilkie Collins' "The Ostler" (Household Words, 1855), a chilling instance of a dream portent, and Rosa Mulholland's "Not to be Taken at Bed Time" (All the Year Round, 1865), a highly regarded tale of Irish witchcraft. Dickens also serialized several cornerstone works of fantastic literature in the regular issues of All the Year Round, most notably Edward Bulwer-Lytton's A Strange Story (1861-1862) and J. S. Le Fanu's "Green Tea" (1869).

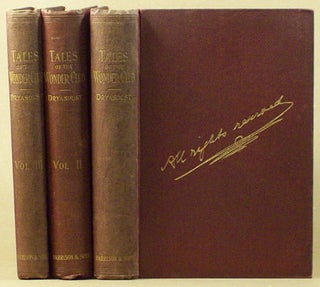

Given the enormous success of Dickens' Christmas annuals, other periodicals quickly followed suit. The first three Christmas issues of Tinsley's Magazine--Storm-bound (1867), A Stable for Nightmares (1868), and Thirteen at Table (1869)--employed the now familiar framing device of people gathered together under various circumstances telling tales, including ghost stories, to entertain themselves or pass the time. Far from being second-rate imitations of Dickens' Household Words and All the Year Round, competitors’ Christmas annuals contained equally excellent examples of the Victorian ghost story. Storm-bound, for example, features Amelia B. Edwards' "The Story of Salome," widely regarded as her best work. The first Unwin's Christmas Annual, The Broken Shaft (1886), in which passengers tell stories while aboard a stranded ocean liner, includes F. Marion Crawford's superb "The Upper Berth," the tale of cabin 105 haunted by the malevolent ghost of a suicide. The zenith of the holiday periodicals are probably the issues of Routledge's Christmas Annual devoted to novella-length ghost stories by J. H. Riddell, especially The Uninhabited House (1875), which E. F. Bleiler considers "probably the finest High Victorian supernatural novel." In addition to the Christmas annuals, publishers also issued single-author ghost story collections specifically tied to the Christmas season, including Rhoda Broughton's Tales for Christmas Eve (1873), a legendary genre rarity, and Mrs. Baillie Reynolds' The Relations and What They Related (1902), a scarce, well-regarded collection. Jerome K. Jerome even parodied the convention of Christmas ghost stories in Told After Supper (1891), a series of tales exchanged during a drunken storytelling session on Christmas Eve.

With the exception of books issued to coincide with the Christmas season, only a small fraction of the ghost stories published during the Victorian era in story collections and periodicals actually take place during the Christmas season. Like Victorian crime fiction writers, authors of Victorian ghost stories proved themselves especially inventive within a range of typical scenarios and settings, often resulting in subtle, sophisticated variations on a handful of central themes. While the ghosts themselves often fall into easily recognizable categories--restless but benign spirits who return to protect loved ones or reveal past crimes, vengeful spirits who wreak havoc on the individuals who have wronged them, and tortured souls whose extreme grief or guilt prevent them from finding eternal peace--the best practitioners of the Victorian ghost story work wonders as they explore social and cultural concerns rooted in urbanization, traditional gender roles, and the expansion of the British Empire. In A Christmas Carol and The Haunted Man, Dickens' yuletide spirits issue strong warnings against the alienating forces of materialism and industrialization, positing generosity and community as necessary correctives to the societal ills plaguing the author's beloved London. Mary Elizabeth Braddon's "The Cold Embrace" (1860) and E. Nesbit's "From the Dead" (1893) serve as condemnations of an oppressive patriarchal society that subjects women to institutionalized forms of abuse and exploitation through marriage and economic dependence. In such stories, the ghosts of dead women typically function as proto-feminists who return to the living in order to haunt the men who have destroyed their lives. The murdered civil servant in Rudyard Kipling’s "The Return of Imray" (1891) and the dead fakir who comes back as jackal in Alice Perrin’s "Caulfield’s Crime" (1892) are harrowing expressions of cultural conflicts arising from the British presence in India. Highly sophisticated, ambiguous tales, like Vernon Lee's "Amore Dure: Passages from the Diary of Spiridion Trepka" (1887) and Henry James' The Turn of the Screw (1898), add a depth of keen psychological insight to hauntings mired in complex issues of sexuality and desire. The sheer number, in fact, of landmark collections of ghost stories published in England and the United States during in the late 19th century--J. S. Le Fanu's In a Glass Darkly (1872), J. H. Riddell's Weird Stories (1882), Amelia B. Edward's Monsieur Maurice and Other Tales (1883), Ambrose Bierce's Can Such Things Be? (1893), and Ralph Adams Cram's Black Spirits and White: A Book of Ghost Stories (1895), to name only a few--confirms the ghost story's status as one of the premiere genres of Victorian literature.

The Victorian ghost story's influence on modern and contemporary horror fiction, of course, cannot be overestimated. M. R. James, a towering figure in the development of supernatural literature in the 20th century, began writing his antiquarian ghost stories in the 1890s to entertain the choristers of King’s College while they waited to perform during services on Christmas Eve. Like Mary Elizabeth Braddon and E. Nesbit, early 20th-century female authors, such as Edith Wharton and Marjorie Bowen, continued to use the ghost story as a vehicle for critiquing gender roles and the transactional nature of relationships between men and women. More importantly, modern and contemporary horror fiction’s obsession with "the return of the repressed" would not exist without the classic Victorian ghost story. With its astute yet subtle examination of mental illness, aberrant psychology, and lesbianism, Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House (1959, arguably the greatest haunted house novel in the history of the literature, is firmly in the tradition established by Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s "The Haunted and the Haunters; Or the House and the Brain" (1859). Taking their cues from B. M. Croker, Rudyard Kipling, and Alice Perrin, in Toni Morrison’s Beloved: A Novel (1987), Hari Kunzru’s White Tears (2017), and Viet Thanh Nguyen’s “Black-Eyed Women” (2017), writers of color craft terrifying expressions of racial and sexual exploitation, as well as cultural concerns about class privilege and immigration, in the form of ghosts of children born into slavery, conjured African-American bluesmen, and dead Vietnamese boat people. Dickens would have certainly shuddered, but he definitely would have been pleased.

Ghost stories, in the end, have always been somewhat claustrophobic--stuffy, closed rooms and shuttered windows with roaring fires that can't quite drive out the evening's chill. As Andrew Smith states in The Ghost Story, 1840-1920 (2010), "Throughout the 19th century, there is a progressive internalization of horror, the idea that monsters are not out there but to be found within … With the ghost story there's a sense that instead of being able to lock yourself away in your home, to leave the monster outside, the monster lives with you, and has a kind of intimacy." The true significance of Victorian ghost stories is frighteningly simple. Like Ebenezer Scrooge, every generation unknowingly, through its shortcomings, forges its own chains socially, politically, morally, and aesthetically. We haunt ourselves. We invite our ghosts in. What, even now, scratches at our windows? Who, as we speak, waits at our doors?

![#113073) MYSTERIES OF THE UNSEEN; OR, SUPERNATURAL STORIES OF ENGLISH LIFE ... [with] WILD AND...](https://lwcurrey.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/113073.jpg?width=320&height=427&fit=bounds&auto=webp&v=1682005293)

![#134545) TALES OF TERROR ... By Dick Donovan [pseudonym]. James Edward Preston Muddock, "Dick...](https://lwcurrey.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/134545.jpg?width=320&height=427&fit=bounds&auto=webp&v=1682006180)